Movement seeds: Supporting early-stage local animal advocacy in Central Asia and the Caucasus

May 21, 2025

January 20, 2020

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with the modern animal rights movement should be well aware that it consists of several factions, one of which is the self-styled “abolitionists”. The abolitionists distinguish themselves from other factions of the movement by rejecting welfare campaigns, and insisting that veganism is a moral baseline and that its peaceful promotion should be the primary focus for animal advocacy2.

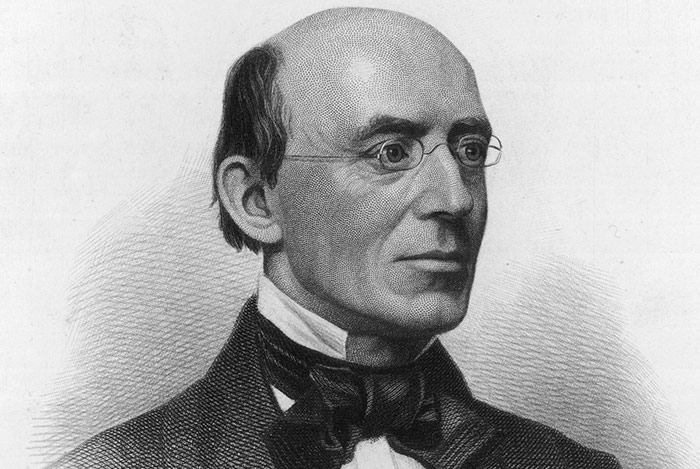

The most well known and influential abolitionist is, no doubt, Professor Gary L. Francione, a distinguished American legal scholar, an author of a half a dozen books on animal rights and related issues, including Rain Without Thunder: The Ideology of the Animal Rights Movement, which is widely considered to be a contemporary abolitionist classic, and the editor of the Abolitionist Approach website3.

When the self-professed animal rights abolitionists try to explain their tactic to the broader animal liberation movement, they usually invoke the example of the 19th-century anti-slavery abolitionists, from whom they took their name4. Here, as an example, is an insightful quote from an article Prof. Francione has published on his website:

Garrison [William Lloyd, one of the most influential 19th century exponents of anti-slavery abolitionism in the US5] was clear: If you oppose slavery, you stop participating in the institution. Period. You emancipate your slaves. You reject slavery and you aren’t ashamed of your opposition. You don’t try to hide it. You openly and sincerely, but nonviolently, express your “persistent, uncompromising moral opposition” to slavery, which is “a system of boundless immorality.”

Similarly, if you believe that animal exploitation is wrong, the solution is not to support “happy” exploitation. The solution is to go vegan, be clear about veganism as an unequivocal moral baseline, and to engage in creative, nonviolent vegan education to convince others not to participate in a system of “boundless immorality.”

It would have been absurd in the 19th century to claim that there was no difference between those who opposed slavery and those who favored its regulation. It is absurd now to claim that there is no difference between those who propose veganism as a clear, unequivocal moral baseline and those who promote the “humane” regulation of animal exploitation and “compassionate” consumption, and who claim that being a “conscientious omnivore” is a “defensible ethical position.”.

Professor Francione is making several claims here regarding the Garissonian version of abolitionism. The quote seems to imply that the 19th century anti-slavery activists regarded abstention from the products of slave labor as a moral imperative (they not only opposed slavery, but refused to participate in it), and they believed that the best way to end slavery was to convince their fellow citizens that keeping other people in bondage was immoral.

If this is your understanding of the 19th-century abolitionism, then the parallels between the “abolition then and now” may seem obvious. Veganism is basically a modern-day equivalent of absenting from the use of the products of slave-labor, and appealing to meat-eaters (and vegetarians!) to “Go Vegan” is an exercise in moral suasion.

The aim of this article is to convince you that while there are in fact some parallels between anti-slavery and animal rights abolitionism, they do not necessarly run along the lines that Prof. Francione is drawing, and that the followers of the “abolitionist approach” are drawing the wrong conclusions from the lessons of history.

The rest of the article is divided into four parts. In the next section I will give a short general overview of the American anti-slavery abolitionism. In the third and fourth sections I will take a closer look at two tactics that Professor Francione is associating with the abolitionist movement — moral suasion and abstention, respectively. The fifth section will conclude the article with some practical suggestions aimed at the modern vegan movement.

Many people nowadays treat the abolitionists and the anti-slavery movement as being one and the same. This is a big mistake. In reality the former constituted only a minority within the latter. An abolitionist was someone who held three closely connected beliefs, and was actively engaged in promoting them among the general public.

First, abolitionists were “immediatists”, that is they believed in an “immediate abandonment” of slavery. They were in favour of emancipation that encompassed all slaves at once, and had no transitional period (there was also another important dimension to “immediatism” that I will touch upon later in the article). Second, they insisted that the emancipation of slaves should be unconditional, that is that it should happen without compensation to the slave owners and without forceful removal of emancipated slaves from the United States. Third, they demanded that the abolition of slavery should be followed by the extension of full civil rights to all freedmen, and the “coloured population” in general6.

All of the above-stated goals were extremely controversial in 19th century America. The insistence of the abolitionists on the immediate and unconditional emancipation, made them the target of hatred and abuse among the southern slave-owners and their political and economic allies. The fact that they demanded equal civil rights for whites and blacks resulted in them being scorned all around the country, including in the non-slave owning North. In the South abolitionists were perceived as dangerous seditionist and “slave-stealers”, and in the North as racial “amalgamationists” or worse.

The prevalence of racism among the Northerners is worth touching upon. Nowadays many people conflate anti-slavery with anti-racism, but in pre-war America “color phobia” was much more widespread than it is today. Even among the people with strong anti-slavery convictions, there were many who believed that while blacks deserved freedom, they were not capable of excercising civil rights, or even competing against free white labor. Therefore many “friends of slaves” insisted that once slaves were emancipated, they should all be removed — “for their own good, as well as the good of the country” — from the United States. This stance, known as “colonization” was very popular among white anti-slavery Americans, and had such influential exponents as Harriet Beecher Stowe (it is no coincidence that at the very end of Uncle’s Tom Cabin the black protagonist of the book emigrates to Liberia), and president Abraham Lincoln, whose administration was making plans for the colonization of British Honduras even after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 18637.

By combining anti-slavery advocacy with a hardline stance against “color phobia” abolitionists made themselves immensely unpopular among the general public, and their views remained a minority position among the US population. At most, no more than 300,000 people self-identified as abolitionists in pre-war America. The US population at the outset of the 1860s is estimated at around 31 million.

The largest abolitionist organization in the US at this time was the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). The AASS was established in 1833 by a small group of radicals representing different religious denominations, professional occupations and social classes. In the next five years their organization rapidly expanded its membership base, and established a very large number of smaller auxiliary societies all around the North. By 1838, it had more than 1,300 state and local chapters that together claimed a membership of about 100,000 people. The AASS eventually grew to around 250,000 dedicated members, who were actively involved in a decades-long peaceful effort to owerthrow slavery.

The American 19th century abolitionists tried to reach their goals by many different means over the years, but the tactic that scholars most closely associate with the Garrisonian wing of the anti-slavery movement (at least in its earliest incarnation), and which Professor Francione is suggesting the modern animal rights advocates should follow, is so-called “moral suasion”. This term encompases a broad range of non-violent forms of agitation — preaching, lecturing, pamphleteering, canvassing, petitioning, etc. — abolitionists used to convince their fellow citizens that slavery is deeply immoral and should be immediately abandoned and atoned for.

Garrison and his followers regarded slave-owning as a grievous sin (an offense against God), and implored the slave owners to free their slaves and repent for the sin of “man-stealing” (a biblical term for slaveholding). The emphasis the abolitionists put on sin and repentance while framing their message is not a coincidence. The early abolitionist movement was essentially a Christian religious crusade, whose ultimate goal was a creation of a “government of God”, in which no man would usurp God’s power over men8.

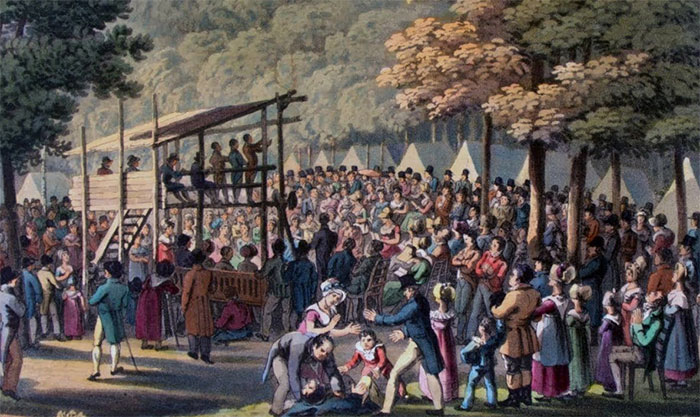

The AASS came into existence on the wave of the so-called Second Great Awakening – a Protestant religious revival that swept the US during the first half of the 19th century9. The leaders of this revival — evangelical ministers like Lyman Beecher, Charles Grandison Finney, and later Theodore Dwight Weld — emphasized the ability of every individual to renounce sin and encouraged their fellow Christians to strive for holiness. Their doctrine came to be known as a “perfectionism”.

As a mass movement the Second Great Awakening had both a religious and social dimension. It aimed at purifying society, by getting rid of impiety, drunkenness, sexual license, violations of the Sabbath, and all other sinful behaviours. Of all the social causes the people associated with the Awakening embraced, two were pursued by them with the most fervor — temperance (abstention from the consumption of alcohol), and the abolition of slavery10.

Before the Second Great Awakening radical anti-slavery advocacy in America was almost exclusively associated with a small sect of Quakers11. In the late 1820s and early 1830s, due to the new religious outpouring, the ranks of abolitionists was quickly swelled by a large number of newly radicalised Congregationalists, Baptists, Methodists and Presbiterians. Believing that slavery was the most God-defying sin of all, this new breed of anti-slavery radicals began “evangelizing the world”, by spreading the gospel of brotherhood and equality of all men.

The perfectionists’ belief that slavery was principialy a sin, and only secondarily an injustice had a major tactical implication. For the abolitionists, the rejection of slavery was first and foremost a matter of personal conscience. A good Christian could not support it, and profit from it even less so. All that was needed for slavery to end was therefore that slaveholders repudiate their sinful ways. Such conversion did not depend on the decisions of a political body or a court of law, and could be accomplished without any intermediate agency (hence the second meaning of the “immediate abolition”).

In practice the idea of “moral suasion” was translated into a massive social campaign targeted at slaveholders, and their political, economic and religious allies on the one hand, and at the people who were sympatethic to the anti-slavery cause but had not yet embraced abolitionism, on the other12.

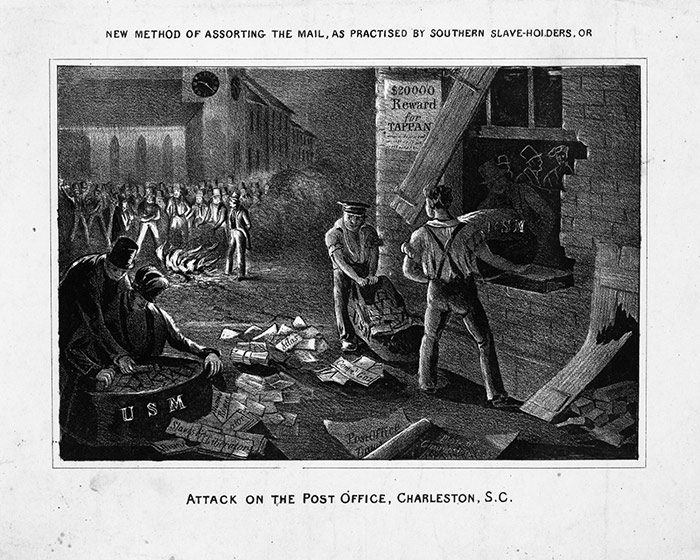

Within a year of its founding, the AASS published and distributed more than 100,000 propaganda items — newsletters, pamphlets, posters, emblems, songbooks, and even readers for small children, and sent them all around the country. The following year the number of items distributed by the abolitionists grew almost tenfold. By 1835, the AASS basically flooded the United States with anti-slavery messages, by sending more than one million pieces of propaganda, with the aim of convincing the Southern slaveholders to free their slaves and advertaising the abolitionist cause all around America.

The abolitionists’ Great Postal Campaign required a very large amount of resources (the cost of postage alone amounted to $30,000, an enormous sum at the time) and involved hundreds of dedicated activists all over the North. Its results, however, were mixed, to put it mildly.

Thanks to the campaign, the AASS managed to quickly establish itself as a premier anti-slavery organization in the US, and the number of people who joined its local chapters and subscribed to abolitionist newsletters grew very quickly. At the beginning of 1835 there were around 200 anti-slavery societies in the North, a year later that number grew to more than 520. During the same period more than 15,000 people subscribed to abolitionist newsletters, a rate of growth which was unprecedented in the history of any American reform movement13.

Seeing their numbers grow rapidly, some more politically-minded abolitionists decided to seize the momentum, and at the end of 1835 they launched another phase of the moral suasion campaign — the Great Petition Campaign for the abolition of the interstate slave trade and slavery in the District of Columbia (issues that were clearly within the constitutional jurisdiction of the federal government). The AASS started circulating printed anti-slavery petition forms among its new members, and encouraged them to collect as many signatures as possible and send them to their local congressman14.

Within a year of launching the petition campaign, abolitionists managed to collect more than 34,000 signatures. In 1837, that number rose to around 100,000, and in 1838 the AASS reported that during the first 3 months of the year the society had collected a “waggon load” of petitions bearing half a million signatures (the petitions were worded in such a way as to appeal to a broad spectrum of people with anti-slavery convictions, and not just to abolitionists alone).

The number of signatures collected under petitions circulated by the AASS was impressive, but it also very clearly demonstrated that anti-slavery voters did not constitute the mainstream of the electorate in the North (even in the abolitionist strongholds no more than 20% of eligible voters had signed anti-slavery petitions). As a result very few members of Congress were willing to submit the AASS’ petitions for discussion.

This cautious and calculated response to the petitions from the northern congressman convinced their southern colleagues that the anti-slavery motions could be easily tabled without discussion, and on May 18 1836, the House adopted the infamous “gag rule”15. It resolved, that ‘“all petitions, memorials, resolutions, propositions or papers, relating in any way, or to any extent whatever, to the subject of slavery, or the abolition of slavery, shall, without being either printed or referred, be laid upon the table, and that no further action whatever shall be had thereon”16. The House renewed the gag rule at the beginning of each session of Congress and in 1840 made it permanent (it lasted until 1844 when it was finally discarded).

Abolitionists did not stop sending resolutions to their congressman, in fact they immediately started to circulate a new set of very popular petitions, this time against the gag rule itself, but by the early 1840s it was obvious to them that even with a growing number of supporters they were unlikely to achieve a significant victory for slaves in Congress, unless the political composition of both houses would change significantly.

The “gag rule” setback aside, the movement building part of the “moral suasion” campaign was clearly a great success for abolitionists. They made themselves heard, the AASS quickly became of one the most important reform organizations in the US and the number of its members swelled dramatically. The part of their campaign aimed at convincing the slaveholders and their allies to abandon the sin of “man-stealing”, however, ended in “unqualified disaster”17.

Of the 20,000 parcels sent by the abolitionists to southern addresses, most never reached their destination. In Charleston, South Carolina, an angry mob invaded the post office, seized the abolitionists’ parcels, and publicly burned them, alongside effigies of Garrison and Arthur and Lewis Tappan (two wealthy brothers, who had made a huge fortune selling silk as an alternative to slave-grown cotton, and used the proceeds to finance anti-slavery campaigns and other perfetionists social causes). In other southern areas, such actions proved to be unnecessary, as the local postmasters, supported by the President Andrew Jackson (a Tennessee slaveholder) himself, took upon themselves to make sure that the abolitionist mailings would not be delivered to the addressees.

People who were suspected of distributing anti-slavery propaganda or even having abolitionist leanings were publicly prosecuted, faced vigilante violence or both. To make sure that no known abolitionist would ever venture a journey to the South, several southern state legislatures voted for cash bounties for the capture of the leading members of the AASS.

The “reign of terror”, as Garrison dubbed the violent events following the Great Postal Campaign, was not confined to the South. Angry mobs followed the abolitionist almost wherever they went, and many times their meetings, lectures and other public gatherings were physically attacked by the members of local communities (quite often with an active involvement or at least with the tacit support of “gentlemen of property and standing”).

Anti-abolitionist violence erupted even in places like Boston, Philadelphia, Utica, Rochester, Pittsburgh, and Syracuse, were the AASS agents could have hoped for sympathetic reactions. In New York City, were the Tappan brothers mentioned earlier were based, and from where the postal campaign was conducted, a mob ransacked Lewis’ house, and burned his belongings (a similar thing happened to Arthur’s Connecticut house as well).

William Lloyd Garrison was almost lynched in the abolitionist stronghold of Boston, and the northern offices of several abolitionist newspapers were attacked, and their printing equipment destroyed. Finally in 1837 Elijah P. Lovejoy, the editor of the abolitionist newspaper the Alton Observer was killed in a gunfight with the angry mob which attacked his office for the fourth time.

In the end, the southern campaign proved to be counterproductive. It actually hardened the commitment of slave-owners and their political allies to slavery. At the turn of the century many prominent Southerners believed that slavery was evil, albeit a necessary one. Even some prominent slaveholders harbored “speculative doubts” about the moral validity of slavery, and openly entertained the ideas of gradual emancipation and colonization. When abolitionists started branding them as “remorseless man-stealers” who were “imbruting” their brothers and sisters, the slave-owners were forced to rethink their positions and to justify their ways, both to themselves, and to the outside world.

One of the most far-reaching, but unintended, consequences of the abolitionists’ “moral suasion” campaign, was the emergence of a new genre of pro-slavery polemical tracts, which quickly became immensely popular among the Southerners. Pro-slavery apologia was obviously nothing new in the South, but the abolitionists’ anti-slavery push became a catalyst for a new wave of increasingly systematic and complex defenses of slavery, that tied the “peculiar institution” very closely with the southern way of life, and made it a cornerstone of a distinct “southern civilization”. Unlike earlier slavery apologists, writers associated with this new era of pro-slavery thought — e.g. Thomas Roderick Dew, William Harper, Thornton Stringfellow, and later George Fitzhugh — collectively managed to create a formal ideology, that provided a basis for a shared identity to a whole generation of white Southerners18. From then on, every attack on American slavery was seen as an attack on the South itself.

The private violence, institutional backlash, and the rapid growth of an extremely hostile southern ideology, severely shocked abolitionists19. It also made them rethink their tactics, as it was obvious to everyone involved that “moral suasion” (or at least one particular mode of it) had utterly failed. It was one thing, however, for the abolitionists to agree on the fact that their tactic was not working. How to deal with the failure was another matter altogether, and it eventually caused an irreparable split within the abolitionist movement20.

From around 1837 to 1840 the American abolitionists were engaged in a very lively, if sometimes virulent, discussion on how to deal with the fallout from their campaigns. Pages of anti-slavery newsletters were filled with polemical articles, acusations, rebuttal letters, and counter-rebuttals. By 1840 three main factions emerged from these discussions within the American abolitionist movement.

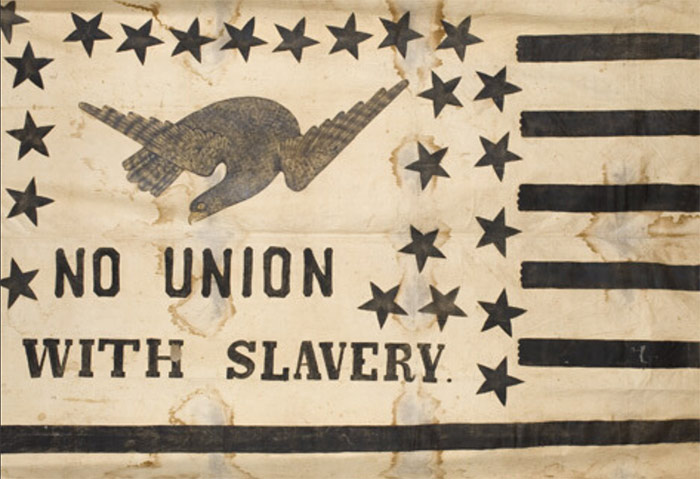

The first faction was led by William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips21. Believing that the violence abolitionists had experienced was just a manifestation of general corruption that permeated through the American society and its religious and political institutions, the Garrisonians, as they were called, started urging the AASS members “to come out from among them and be separate” (2 Corinthians 6). Following their lead a substantial number of abolitionists ostentatiously left churches unresponsive to the anti-slavery message, rejected electoral voting and public office holding, argued against abolitionists’ involvement in political parties, and eventually started calling for northern secession under the banner of “no union with slavery”. Some, including Garrison himself, became so radical in their disavowal of politics and organized religion that they became known as “no-government men”.22

On the more positive side, the Garrisonians helped launch a number of successful campaigns against “color-phobia” in the North — e.g. against segregated public transport, and public schooling, as well as for black enfranchisement — and were actively involved in fighting against the Fugitive Slave Law, and providing help to runaway slaves.

The second faction led by Elizur Wright Jr., Joshua Levitt and James Gillespie Birney, formed the political wing of the abolitionist movement. Unlike the Garrisonians, who regarded the US Constitution as a ”covenant with death, and an agreement with hell”, members of this faction, still believed in a republican form of government, and put much hope in effecting positive change through the electoral system. Seeing however that no existing political party was willing to commit itself to the cause of abolition, or even to reject the “gag rule” that had been trampling the abolitionist’s petition drives, they decided to form a new political organization, the Liberty Party23.

The Liberty Party was a “one-idea party”, it sole aim was to end slavery via “the absolute and unqualified divorce of the general [i.e., federal] government from slavery, and also the restoration of equality of rights among men, in every State where the party exists, or may exist”. A purely abolitionist party proved to be an idea ahead of its time. The best electoral outcome for the LP, the 63,000 votes its presidential candidate James G. Birney (a former slave-owner turned abolitionist) received in 1844, represented an insignificant percentage of the popular vote. Therefore in 1848 most of the “Liberty men” decided to join forces with a number of disillusoned anti-slavery Democrats and Whigs, and form a new party, with less radical aim of stoping the growth of “slaveocracy” and the expansion of slavery into newly acquired western territories.

The so called Free Soil Party quickly became a major political force in the North. Its first presidential candidate received more than 10% of votes in 1848, and the party managed to send several of its members to the US Congress. Eventually in 1854, the Free Soil Party merged with the newly created Republican Party, and some of its former members like Salmon P. Chase (a longtime chairman of Liberty Party in Ohio), Charles Sumner and John P. Hale became leading voices of anti-slavery agitation in the federal legislature24.

The third faction led by Lewis Tappan, Amos Phelps and William Jay decided to stick to moral agitation, but frame it more conservatively, and make it more “respectable” by cleansing it from any form of religious radicalism and nascent feminism that was gaining traction among the Garissonians. To this end they formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1840. The new organization was modeled after the similarly named British society, and stayed in line with the orthodoxy of English abolitionism. It recognized “the lawfulness of human government”, urged its members to vote and participate in established political parties, declared women’s active involvement in reform organizations as “repugnant to the constitution of society” and distanced itself from “come-outerism”, “no-governmentism” and other Garrisonian “heresies”.

Even though the AFASS could count on large financial support from the Tappan brothers, who “could not swallow Garrison” and his growing radicalism, the new organization dwindled rather quickly. With Tappan’s money and editorial talents of Joshua Leavitt the society managed to publish and distribute a number of anti-slavery newsletters and tracts, but was largely inactive between annual meetings and had difficulty attracting new members. Eventually, in 1855 the AFASS stopped holding regular annual meetings, and in 1859 folded completely. It is now recognized by historians as “the weak wing” of the US anti-slavery movement25.

The post-1840 history of the American abolitionist movement was marred by bitter factionalism and a long-lasting personal animosity between its leading members. The lines dividing the movement were not drawn, however, between those who “opposed slavery unequviocally” and those who “favored its regulation”, but between different factions of commited “immediatists”, who could not agree on how to deal with the failure of the moral suasion campaign. The rift between the sides never properly healed, and some of the AASS founding members stayed permanently estranged, but over the next two decades the two main factions of the abolitionist movement slowly embraced an institutional type of campaigning, and sometimes even combined their efforts in joint campaigns26.

By 1860, when the moderately anti-slavery Republican Party won control of both houses of Congress and its candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected President, even the Garrisonians started to focus their efforts mostly on pushing the Republicans towards more abolitionists positions. When the Civil War finally broke, the long-divided abolitionist movement reunited around the call to transform the war for the preservation of the Union into a “war of abolition”27. Once the emancipation was accepted by Republicans as a “military necessity”, the abolitionists started to collectively push for constitutional amendments that would secure the freedom for slaves by abolishing and prohibiting the institution of slavery in the United States forever and awarding all freedmen full civil rights28.

There is no consensus among the historians of the movement on how to evaluate the AASS efforts to end slavery. Early scholars tended to see the “immediatists” as religious fanatics who were oblivious to economic and political realities29. Modern research is much more favourable towards radical abolitionists and their tactics30. There is however no doubt among the historians of the movement, that for most of the abolitionists “moral suasion” was just one of many approaches they had tried to end slavery, and that it gave way to institutional and political strategies once it became clear that Southerners were not inclined to repent and free their slaves voluntarily31.

What about “abstention”? Did the 19th century abolitionists really regard it as an unequivocal moral baseline, and a true test of the commitment to the cause, as Professor Francione is implying? The answer is an emphatic “no”32.

Abstention was first used as a tactic by British abolitionists in late 18th century33. The crux of the campaign was the boycotting of slave-produced sugar from the West Indies (now known as the Caribbean Islands). The goal of the boycott was basically economic. The campaigners wanted to end slavery by making it unprofitable. As one British abolitionist explained, ‘If sugar were not consumed, it would not be imported—if it were not imported it would not be cultivated, if it were not cultivated, there would be an end of the Slave Trade”34.

The British West Indies sugar boycott attracted a mass following35. According to some modern estimates, at the height of the campaign, at least 500,000 people participated in it. The economic goal, however, was not reached, as the campaigners were not able to influence the long term price, hence the profitability, of slave produced sugar. Nevertheless their effort was not without results. The boycott helped to launch a mass movement of dedicated abolitionists who by engaging in more traditional forms of campaigning — like petitioning and canvassing — eventually managed to convince the members of the British Parliament to pass the Emancipation Act in 183336.

The idea of abstentionism was transplanted into the US in the 1830s, with the republication of a small pamphlet entitled “Immediate, Not Gradual Emancipation” written by an English abolitionist Elizabeth Heyrick37. Heyrick’s essay was originaly published in 1824, partially as an appeal to the British abolitionists and partially a challenge to the leaders of the local anti-slavery movement. Believing that campaigning based on “reason and eloquence, persuasion and argument” was ineffective in the face of the huge profits made by the slave owners, she urged the abolitionists to engage in “something more decisive, more efficient than words”, that is to participate in an organized abstention push, that would undermine the economic basis of slavery. According to Heyrick, all that was needed to give “the death blow” to slavery was for “friends of the poor degraded and oppressed African” to solemmnly and irrevocably bind themselves to no longer purchase the products of slave labor.

“But what can the abstinence of a few individuals, or a few families do, towards the accomplishment of so vast an object?” It can do wonders. Great effects often result from small beginnings. Your resolution will influence that of your friends and neighbours; each of them will, in like manner, influence their friends and neighbours; the example will spread from house to house, from city to city, till, among those who have any claim to humanity, there will be but one heart, and one mind, — one resolution, one uniform practice. Thus by means the most simple and easy, would [...] slavery be most safely and speedily abolished”38.

Heyrick’s critique of moral campaigning struck a chord with American abolitionists who by the middle of the 1830s had become disillusioned with the prospect of ending slavery through “way of argument” alone, and were ready to pursue new tactics. It also appealed to their perfectionist sensibilities, by promising all those who “wash[ed] their own hands in innocency”, a personal reward in the form of ”consciousness of sincerity and consistency, -of possessing ‘clean hands’, of having ‘no fellowship with the workers of iniquity’”39.

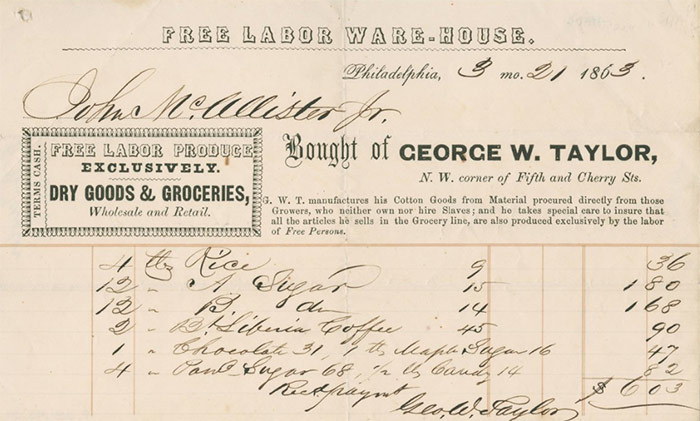

Given the circumstances in which the American movement had found itself in the late 1830s, it should not be surprising that the initial response of the American abolitionists toward abstention was mostly enthusiastic. They quickly set up more than 30 local associations promoting abstention, and opened more than 50 “free produce” shops, which sold free labor goods exclusively.40

In one respect the American proponents of abstention proved to be even more radical than the British ones who had influenced them. The British abstentionists called for the boycott of just one commodity – sugar. The Americans called for a boycott of all slave-produce – sugar, rum, rice, tobacco, and most of all, cotton and everything that was made out of it.

The American abolitionists’ initial enthusiasm for abstention and free produce waned rather quickly, however. There were several reasons why the “abstention movement” did not attract a large following in the US, even among the Americans with anti-slavery convictions.

First of all, the complete avoidance of the products of slave labor proved to be much more challenging than boycotting sugar only. There were very few local alternatives to slave-produce, and importing them from abroad was costly and logistically challenging. The supply of free labor goods was not sufficient to satisfy even the smallest demand, and as a result the free-produce shops regularly struggled with inventory shortages.

Moreover, the prices of free labor goods were usually much higher than the slave produced alternatives, and many prospective customers, especially free blacks and white working-class abolitionists, could not afford to buy them41. On top of that, the quality of the products was often low. As one abolitionist later recollected, “free sugar was not always as free from other taints as from that of slavery; and free calicoes could seldom be called handsome; free umbrellas were hideous to look upon, and free candies, an abomination”.42

In the end, the exclusive reliance on free produce required so much self-sacrifice and dedication to the cause that only the most committed abstentionists could maintain it. More worryingly, some prominent proponents of abstentionism started to gradually concentrate their efforts on abstention, to the detriment of other anti-slavery activities. This last phenomenon become the major issue of contention between the followers of abstention, and the broader American abolitionist movement in the 1840s.

Some pragmatic abolitionists were sceptical towards abstention from the very beginning. As early as 1836, when the abstention campaign was just starting to gain traction among the American abolitionists, Elizur Wright Jr. commented on its futility.

“To practice a total abstinence, we must not only lay aside slave labor sugar and rice, but all cotton fabrics, and those of which cotton is any part. Our merchants and manufacturers must throw perhaps half their stock and their capital into the fire. The property thus sacrificed would amount to ten times the sum ever expended in the prosecution of the anti-slavery cause, and the loss would very much impair the ability of abolitionists to give hereafter. But all this is a mere trifle.

No anti-slavery agent, or other abolitionist, must now travel in stage or steam-boat, for the sheets and the table cloths of the latter are of cotton, and the former has its top lined with calico. No abolitionist can any longer buy a book, or take a newspaper printed on common paper [at that time most printers used the so-called rag paper, which was made out of used cotton cloth]. The society must suspend all its publications till it can import or manufacture, at a greatly enhanced expense, paper of linen.

Indeed, if the principle that the use of slave labor products is sinful, had been adopted at first, the anti-slavery reformation could not have started an inch. If it should be introduced now, it would immediately stop. We hardly need say that such a result would greatly encourage slavery. For even suppose that all who profess to be abolitionists, should have come up to the point of total abstinence supposed, it would not diminish the demand for cotton a hair's breadth. Among the constant fluctuations of the market, the deficiency would no more be perceived than a drop from the ocean”43.

By the 1840s even the Garrisonians, who initially were sympathetic towards the free produce cause, started criticizing abstentionism not only as impractical, but also as narrow-mindedly moralistic, deeply divisive, and therefore harming the anti-slavery movement. It was bad, Garrison claimed, that the abstentionists were “so occupied by abstinence as to neglect THE GREAT MEANS of abolishing slavery”. What was worse however, was that some of them treated abstention as a “test of moral character”, and therefore questioned the commitment of the non-abstaining abolitionists to the cause of ending slavery44. In practice their effort to “cleanse their hands of the dark red stain of slavery”, was dangerously close to transforming the abolitionist social and political campaign into “an endeavor after personal purity”, which — Garrison argued — no slaveholder would fear.45

The abstentionists’ obsession with “clean hands” proved to be a major problem to the owners of the free-produce shops, who constantly had to reassure their clients that the products they were selling were free of slave labor. The suspicion that products sold in “free labor” shops were not really free, was hampering the sales of free labor goods to the point that the American Free Produce Association was forced to start issuing regular statements on the origin of the items distributed by its members46.

Eventually, the self-righteousness of the abstentionists became unbearable even to deeply religious abolitionists, who were still striving for holiness in their own private lives. By the late 1840s, most of the major figures within the American anti-slavery movement had come to oppose abstention, and as a result, in the 1850s abstentionism came to be associated almost exclusively with a very small fraction of Quakers, who mostly distanced themselves from the greater abolitionist millieu47.

According to modern estimates, the total number of members in the free produce associations did not exceed fifteen hundred, and the number of people who patronized free labor shops exclusively may not have reached more than six thousand48. The American Anti-Slavery Association at that time could mobilize more than 200,000 active members.

The American free produce efforts were therefore a failure, both as an economic venture and as a social movement. The failure of this mode of campaigning should not be surprising, however. The American abstention campaign was bound to fail.

The abstention campaign was a combination of a commodity boycott and a buycott. There are many factors impacting the success of a commodity boycott, but the most important one is the availability of suitable substitutes to the boycotted commodity. “Suitable” in this case means 1) easily accessible, 2) reasonably priced and 3) of good-enough quality49. None of these requirements were met in the case of slave-produce. No wonder then, that so few people took part in the boycott.

As one historian of the American abstention movement concluded “free produce failed because it made too heavy an economic demand on the individual. Voluntary self-denial can be expected only of the conscientious few, never of the mass”50.

Professor Francione is wrong in his analysis of the original abolitionist movement. He is mistakenly conflating the abolitionists and the abstentionists, and treats William Lloyd Garrison as a representative of the latter group. This is not just a historical error, which could be easily dismissed by the fact that he is not a historian of social movements (very few people are). Professor Francione’s mistake has major tactical implications, however. By insisting that veganism is a moral baseline and its non-violent promotion should be the primary focus for animal advocates, he and other proponents of the “abolitionists approach” are making a very similar mistake to the one the 19th century American abstentionists made, when they were insisting on abstention being the true test of one’s commitement to the slaves’ cause, and were regarding its promotion as “ the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of [...] slavery”.

Compare, for example, the following quote from Prof. Francione with the previously quoted Elizabeth Heyrick statement on her hopes for the original abstention campaign:

“If every person who is vegan and who believes that veganism is a moral imperative convinced one other person to go vegan in the coming year, and this pattern repeated itself over a period of years, the world would, indeed, be vegan in a relatively brief period of time. For example, a low estimate of vegans in the United Kingdom is 150,000 and the total population is approximately 65 million. If each one of those 150,000 people convinced one other person to go vegan in the next year, there would be 300,00 vegans next year and if this pattern repeated itself for an additional eight years (600,000, 1.2 million, 2.4 million, 4.8 million, 9.6 million, 19.2 million, 38.4 million, 76.8 million), the United Kingdom would be vegan”.51

Of course, Prof. Francione is well aware that the above scenario is unrealistic, and readily acknowledges that it “is not going to happen”52. This realisation doesn’t stop him, however, from claiming that his thought experiment “does show how much more effective vegan education and advocacy can be if we choose to promote it rather than to pursue the welfarist campaigns and single-issue campaigns that promote continued animal exploitation”.53

Given what we know from studies of the past reform movements and social psychology I find this conclusion very unlikely54. Prof. Francione’s approach to campaigning combines two failed tactics of the 19th century abolitionist movement — moral suasion and the promotion of abstention. He may, of course, claim that today those tactics would work better, maybe because modern people are more willing to follow ethical arguments, or because we have much better tools for spreading ideas available, but the odds are against it.

People are social animals, and most of us take cues on how to behave from other people55. As a general rule, we do not want to stick out of the crowd (or to be more precise out of our “reference networks”), and rarely express views or exhibit behaviours that fall outside of the widely held consensus. This is a big problem for vegan campaigners, because in our current culture the consumption of animal products is almost universally seen as normal, natural, necessary or even “nice” (i.e. delicious and fulfilling)56.

People in general do not regard the use of products derived from animals as wrong, because almost everyone in their social circle is using them on a daily basis, seemingly without facing any ethical difficulties. Our collective attitude towards meat and dairy consumption is reflected in a sort of a “social tautology” — most people consume animal products, because most people consume animal products57.

Therefore when we are confronted with arguments questioning our dietary habits and beliefs our unfortunate, but natural, reaction is to become defensive. We immediately look for reasons that could justify our ways, and have many different cognitive biases that we employ to our rescue58. “Everyone is doing it” may not be a strong ethical argument, but for most people it seems to be convincing enough.

It should not be surprising therefore, that despite several decades of relentless campaigning by various animal rights groups, the number of vegans and vegetarians in most western countries is still relatively low — usually below 5% of the population — and barely growing (sometimes we can find some temporary spikes in survey data but they usually don’t last long)59.

For example, in the US, where Prof. Francione is based, only around 1% of adults both self-identify as vegetarians and report never consuming meat. This percentage has not changed substantially since the mid-1990s. The percentage of adults who report not consuming any meat (including fish) on two non-consecutive 24-hour periods has grown since 2003, but still remains below 1.5%. As for the number of self-identified vegans, it is much lower than for vegetarians, and hovers around 0.5%60. While in other western countries the percentages are higher, the animal rights movement is still very far from convincing a significant number of people to ditch animal products from their diet (much less from their wardrobe or life in general).

Now, Professor Francione may be claiming that the meger results of vegan campaigns are just a consequence of a wrongly framed message the campaigners are spreading among the public. According to him, veganism is not a dietary or even a lifestyle choice, but a moral baseline, and should be presented as such. If one views veganism as a “consumer lifestyle”, one can easily choose one of many competing lifestyle models instead. Therefore, the argument goes, veganism should be presented as an ethical necessity, a bare minimum that a decent person can do for animals, and not something one can choose (or reject) for various reasons.

However, when tackling the problem of animal exploitation we are dealing not only with individual attitudes, but — as I noted earlier — also with social norms, that are almost universally observed and reinforced by cultural and religious traditions. Framing veganism as a purely ethical issue may make the corresponding attitude change even harder than it already is. Few people are open to rationally discuss the validity of norms and practices that have been followed for a very long time by the vast majority of their peers, and that are widely regarded as completely natural and right61. As Cristina Bicchieri notes, “if the issue being discussed is emotionally loaded, as is often the case when discussing core values and especially in cases of moral dumbfounding, where people have strong moral reactions but fail to establish any kind of principle to explain their reactions, arguing about the issue may prompt the listeners to stonewall the argument”.62

But, even if the above take is too pessimistic and individual attitude change with regard to the treatment of animals is not as difficult to achieve as suggested above, this doesn’t get us much closer to the goal of animal liberation. As animal advocates we are aiming at behavioral change. We want people not only to change how they think and feel about animal use, but also how they act in their daily lives.

A large body of careful and well replicated social research conclusively shows that personal attitudes are weak predictors of behavior63. Our choices are not based on attitude alone. In fact, often there is a clear gap between our beliefs and our behaviour. Probably the most telling example of this phenomenon was observed among ethics professors.

A few years ago, E. Schwitzgebel and J. Rust conducted a study to check whether professional American ethicists behave better on average than other professors, or if not, do they at least behave more consistently with their expressed values. The answer to both questions is an emphatic “no”. This was also true with regard to eating meat. Even though the ethicists in general showed more concern toward the plight of farmed animals than their non-ethicist peers (most of the former agreed with a statement that eating meat is morally wrong), they were no more likely to be vegetarians than the professors who were not specialising in ethics.64

One may be tempted to blame this disconnection between expressed attitudes and behaviour on hypocrisy, but as should be obvious by now, there are many more factors at play here. Again, our choices are not made in a vacuum. The consumption of animal products is a social norm, and our surroundings reflect it. Shops, restaurants, fast food joints, and public canteens cater mostly to omnivores. Animal farming in most western countries is subsidised with large amounts of taxpayer money, and both private and public institutions are heavily involved in the promotion of animal products. Availability, prices and convenience strongly favor following a lifestyle based on animal use and make the alternatives less appealing.

Therefore, as the authors of the 2015 Chatham House study on pathways to lower meat consumption note, raising awareness about an issue is a good first step but not a solution. “At the point of purchase [...] more immediate considerations – both conscious and subconscious – have more sway over consumer decisions [then their attitudes]. Price, health and food safety have the greatest bearing on food choices, while subconscious cues offered by the marketing environment influence an individual’s automatic decision-making. Consequently, strategies focused only on raising awareness will not result in societal behaviour change”65.

Animal advocates quite often lose sight of how challenging it is for others to follow a vegan lifestyle. Long-time activists in particular tend to live in a bubble. We are usually surrounded by many other like minded people, we are rarely confronted with the necessity to explain our choices to our peers, we have no trouble finding animal-free alternatives to popular products, and we seldom find ourselves in social settings where our commitment to the cause of farmed animals is seriously tested.

Veganism is easy when you are surrounded by other friendly vegans, and live in a big city where there are many businesses which readily respond to your various needs. However when you are the only vegan in your reference group, you may find yourself constantly challenged by people whose attitudes, judgements and opinions you care about the most, and by your surroundings which were designed to make life easier to those who follow the social norms that are contrary to your beliefs.

That this is a serious obstacle to the promotion of veganism is clearly shown by the very large number of lapsed vegans and vegetarians. The unfortunate, but often unacknowledged reality, is that most people who try going vegan, or even vegetarian which is significantly easier, fail to adhere to their diets. Surveys show that at any moment in time there are three times as many lapsed vegetarians than observant ones66. A relatively recent analysis conducted by Faunalytics, suggests that in the US the dropout rate may be even bigger. Only one in five vegans and vegetarians in the US sticks to their diet for a prolonged period of time. Most relapse within a year. Around a third do not even last three months67.

When former vegetarians/vegans were surveyed on why they decided to stop following the diet their most frequent answers were that they had experienced some sort of social or consumer inconvenience, most importantly a lack of sufficient interactions with other vegans and vegetarians. Many former vegans and vegetarians explicitly stated that they disliked the fact that their diet made them “stick out from the crowd”, and more than a third reported experiencing various domestic difficulties resulting from the fact that they were living with a non-vegetarian/vegan significant other. Significantly, only a very low percentage of former vegans and vegetarians surveyed stated that they experienced a shift in ethical thinking68.

As S. Donaldson and W. Kymlicka explain, in general “people do not revert to meat eating for ideological reasons — they do not suddenly reconvert to ideologies of human supremacism — they simply find it too difficult to follow through with their ethical commitments in a context, where none of the everyday unreflective habits and social cues of their lived environment supports those commitments”69.

Does it all mean that animal advocates should abandon the promotion of veganism as a hopeless cause? Not necessarily. But if we are interested in making veganism into a compelling, attractive, easy-to-follow and eventually commonplace everyday practice, and not just a virtue signaling tool for rare individuals who derive a feeling of righteousness from being social outliers, our campaign tactics need to take into account the social and institutional reality that impedes the mass adoption of the animal-free lifestyle70.

First, animal advocates need to make veganism easier. Animal-free products need to be widely available, reasonably priced and of good-enough quality for people to even consider them a suitable alternative to the products of animal industry. To achieve this we need to go beyond the already existing vegan market nische. Setting up all-vegan businesses and encouraging newly converted vegans to patronize them exclusively will not work. Suitable vegan options need to be available in all places where regular people already shop, eat and socialize. Otherwise we will turn veganism into abstention, and it will become yet another victim of a collective action problem (few people are willing to make inconvenient consumer choices, if they perceive that they are making sacrifices that others are not required to make).

Second, animal advocates need to make veganism social. As previously noted, our attitude and behaviour is shaped by people whose judgement and opinions are important to us. Peer pressure, both positive and negative, is one of the strongest influences on decisions we make. Therefore it is crucial that activists promoting veganism find ways to include people who are trying to go vegan into a larger supportive community that can constitute an expanded reference network to the latter71.

Third, animal advocates need to stop spreading the “all or nothing” approach to veganism. Contrary to what many advocates claim, veganism is not “easy”, or at least not everywhere, not always and not to everyone. By insisting on purity and unequivocal dedication to the cause we are raising the bar of admission to the “vegan movement” even higher. This may work as a demarcation tactic, but it is not a good recipe for an inclusive, welcoming and therefore growing community. Following Garrison, one can even claim that by making veganism into “an endeavor after personal purity”, those who insist on unequivocal veganism being a “moral baseline” are creating not a social movement but a quasi-religious cult, which no animal industry will fear, because no animal industry will notice it.

Last but not least, we need to combine vegan advocacy with institutional and welfare reforms. The billions of animals that are currently being held at factory farms in horrific conditions are not affected by the fact that you and I are vegan. It is possible that with the rise in numbers of vegans and other people interested in animal-free alternatives to products of conventional farming practices, the number of animals raised in cruel conditions will steadily fall. But we should not abandon the animals remaining at factory farms at the mercy of those who see the very concept of animal welfare as an impediment to high output and profits, nor to those who claim that by campaigning to make it more expensive and less convenient to raise and consume animals, we somehow fail as animal advocates. Animal farming will not be banned after a short campaign, and neither will society become a hundred percent vegan in a few years. In the meantime, there are many incremental steps we can take to improve the lives of farmed animals that do not fall within the scope of purely vegan campaigning: fighting to ban the cruellest farming practices and convincing retailers to completely remove products of those practices from their shelves (something that is already happening with regard to caged eggs, foie gras and to a lesser extent with fast growing broiler chickens), fighting against agricultural subsidies that benefit the animal industry and requiring the animal industry to pay all externalized costs (hence make their products more expensive and less attractive to consumers), encouraging the fast development of slaughter-free meat and animal-free dairy products so that people can still follow their tastes, without causing harm to animals, etc.72

By combining all those efforts we can gradually rearrange our social environment to the point where regular people are unconsciously making everyday choices that do not harm animals. The incremental change of social habits will need at least the tacit support of a large percentage of active population, but this is easier achieved than trying to convince each and every person that she needs to make personal sacrifices in all those situations where others just follow well established social norms. As Martin Balluch explains, “to try and convince individual people, person for person, is a tactic which cannot but fail, as long as the system is not changed. That is so, because the system in society determines the behaviour of people in it. In an extremely speciesist society, to live vegan costs an enormous amount of energy, so that only a tiny minority will ever have enough motivation and resolve to be able to sustain it for longer. On the other hand, a system in a society that does not provide animal products, will automatically make people lead a vegan life, and latest in one or two generations of young people growing up in a vegan society, the awareness of animal rights will follow”73.