What Anima International did in 2025

December 31, 2025

January 23, 2026

On Monday, in a joint statement, the Norwegian meat industry announced one of the greatest improvements in the quality of life for millions of chickens in history. Norway – where over 70 million chickens are raised for meat every year – will become the first country in the world to stop using fast-growing chicken breeds.

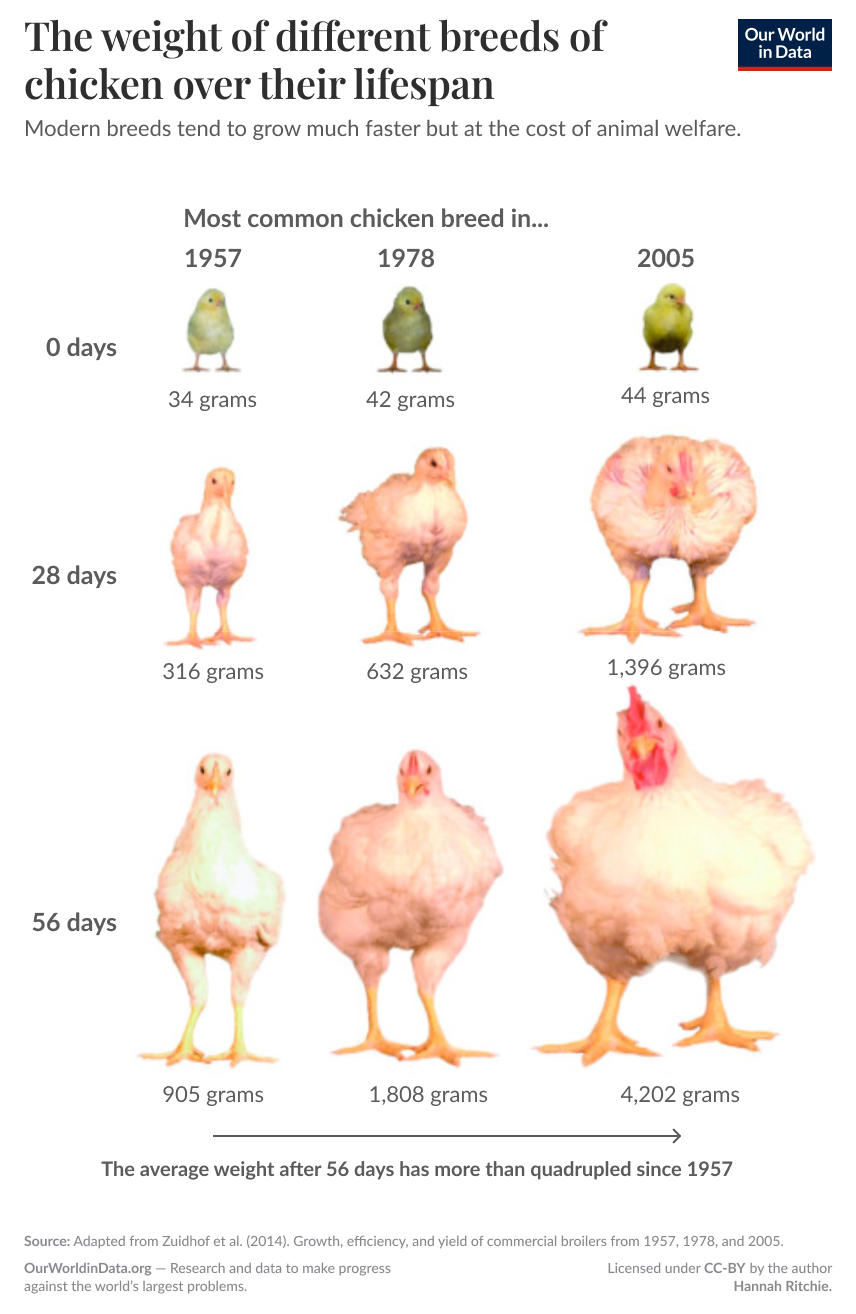

This announcement is a cause for celebration for everyone who cares about animals. The breeding of fast-growing chickens is one of the biggest sources of animal suffering worldwide. Most of the world’s chicken meat comes from birds belonging to the Ross 308 and Cobb 500 strains. These breeds are genetically selected to gain as much weight as possible in the shortest time. Chicken growth rates have increased by over 400% since the 1950s. The industry’s relentless focus on profitability comes at a cost of enormous suffering.

The birds’ muscles grow much faster than their hearts, lungs, bones, and ligaments can cope with. This causes many health problems, the most widespread and serious of which is lameness. Prolonged pain stops the chickens from walking normally and performing other natural behaviors, such as foraging. In the most extreme cases, the birds are not able to move at all, suffering chemical burns from lying in their own excrement.

The chickens’ internal organs often fail to keep up with the body’s high oxygen demands. This leads to fluid buildup in the stomach. The birds feel a growing, distressing sense of breathlessness, eventually leading to a long and painful death.

This is an ethical crisis that cannot be solved through better housing or management – suffering encoded into the birds’ DNA and virtually inevitable. Researchers estimate that an average Ross 308 chicken spends 708 hours in various levels of pain. That’s almost the entire time they are awake during their short and intense lives that typically last only 42 days.

The life of the parent birds (breeders) is even worse. To be able to reach reproductive age, they need to be stopped from gaining weight despite their genetics. This means forcing them into a chronic state of hunger, which researchers from the Welfare Footprint Institute described as “the greatest source of physical pain” that any individual chicken can endure. They also live much longer than their offspring raised for meat.

For these reasons, we consider the use of fast-growing breeds the most urgent problem to eliminate in many countries where we’re active. For the past six years, we have been campaigning in Norway to make the industry transition away from this practice. We targeted retailers and restaurant chains (most notably McDonald’s) in public protests, getting the consumers and media behind. But a lot of this work was much less visible – persistent meetings, documentation, reports, and continuous dialogue with the industry. It is great to finally see it paying off.

But in other countries, the industry is more resistant to change. In the UK, where we’re also focusing on ending the suffering of fast-growing chickens, the progress has been more challenging. We have exposed the cruelty of chicken farming in several investigations, and joined forces with other advocacy organizations to get the industry to adopt the Better Chicken Commitment (BCC) standards. We’ve seen some successes recently, with major retailers Waitrose and Marks & Spencer eliminating fast-growing breeds from their supply chain. Other retailers committed to giving the birds more space. However, fast-growing breeds still make up 90% of the UK chicken industry. And as long as these breeds exist, the most severe suffering will continue.

Of course, any farming improvements that lessen the chickens’ suffering are welcome. In Norway, having now secured the most important step, we will continue to fight for a better life for these animals. The transition away from fast-growing breeds means that the industry must establish new, necessary production areas. We will urge them to take this opportunity to give chickens more space, in line with the European Chicken Commitment (the European version of the BCC) standards.

It’s important to emphasize that the change in Norway did not come through policy, but from the industry itself. It shows that public pressure and changing consumer expectations can force the industry to prioritize animal welfare, even at the cost of reduced efficiency. We can see subtle signs of our work affecting this cultural shift. The term “turbokylling” (“turbochicken”), coined by Anima in Denmark and Norway, has become the most established and penetrating term in Norwegian public discourse about this issue, making its way to official dictionaries. People care about farmed animals and want them to be treated well. The industry can’t ignore us.

We’re grateful to all the advocates, supporters, and donors who made this change possible with their compassion and countless hours of work. Consistent, long-term engagement and maintaining constant pressure and dialogue with the industry seems to be an important vehicle for giving farmed animals a better life. Norway’s historic decision proves that industry change is possible – but millions of chickens worldwide still suffer. You can help us in our fight to end the suffering of fast-growing chicken breeds in other countries. Donate today to give farmed animals a chance at a better life.

Acknowledgements:

Anna Bearne, Jakub Stencel, Anna Kozłowska

Niklas Fjeldberg is the Executive Director of Anima in Norway. He has experience leading national campaigns, engaging with media, and working closely with companies to improve animal welfare. His work has focused particularly on chickens raised for meat. He has also been involved in issues related to corporate accountability and food industry practices.